US/Mexico Border Wall

From border to wall.

On June 16, 2015, Republican Donald Trump launched his run for the office of President of the United States of America with a speech focused largely on immigration across America’s southern border. During his announcement speech Trump said,

— Republican Donald Trump, June 16, 2015“I will build a great wall—and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me—and I’ll build them very inexpensively. I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words.”

Since then, the border shared by the United States and Mexico has been the focus of much discussion and debate. How open should the border be? How should America balance a desire for security with its history as a nation of immigrants? What fears about undocumented immigrants are legitimate, and which are the products of racism or other forms of bias?

By most accounts, building a wall that spans the US/Mexico border would be a daunting and expensive task. Much of it would need to be built on private land, and terrain at various points makes building a wall on or near the border a difficult proposition.

Experts also wonder if the wall—no matter what form it takes—would be an effective deterrent to undocumented immigration across the southern border into the United States.

As President Trump continues to work to secure funding and support for the border wall, Americans might be well-served to ask themselves: Why build a wall? What is it meant to accomplish? And what does the wall actually mean, not just as an architectural feature, but as a symbol?

From Open to Closed

The border between the United States and Mexico is relatively new, and the hardening of that border is even newer.

The border shared by Mexico and the United States is long—1,969 miles long, to be exact. Much of the border was set by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which brought the Mexican-American War to an end in 1848. The 1853 Gadsen Purchase moved portions of the border south. From there, the border was largely set. The border cut in straight lines from west to east, defining the southern edges of what would become California, Arizona, and New Mexico. Where Mexico meets Texas, the border then follows the Rio Grande river in its twisting course to the Gulf of Mexico.

For much of its first 75 years the US/Mexico border was mostly open and unpatrolled save for a few “mounted guards.” It wasn’t until 1924 that Congress established the United States Border Patrol to police the traffic and commerce between the two neighboring countries.

At various stages throughout the twentieth century, the US government has acted to reinforce the Border Patrol with increased staffing and resources, often in response to perceived cross- border threats. In 1993 the US government erected fencing in San Diego, El Paso, and other border towns in response to increases in drug smuggling. But the true hardening of the border would come almost ten years later.

The Secure Fence Act of 2006.

America, post-9/11: In the midst of culture-altering wars, the prevailing feeling is that, in order to prevent future terrorist attacks, America must secure its borders. In response, the Secure Fence Act of 2006 quickly moved through both chambers of Congress before being signed by President George W. Bush. The bill garnered wide support from Republicans and Democrats alike, with then-senators Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama voting in favor.

The bill provided support for an additional 600 miles fencing and other infrastructure along the border, as well as funding for equipment and “smart border” technology, including cameras, sensors, and unmanned aerial vehicles, that would monitor activity at the border and beyond.

The Border Wall, Today & Tomorrow

Illegally crossing the US/Mexico border is a dangerous and sometimes deadly ordeal. Why would anyone take that risk?

Every year, an estimated 350 million people enter or leave the United States through its southern border, and around 400,000 cross over into the United States without documentation. While the border has been strengthened considerably on the United States side, instead of a single barrier, an amalgam of sensors, cameras, walls, fencing, patrols, and aerial support vehicles provide resistance to movement across the border in places other than designated ports of entry. In spite of this, only an estimated 40-55% of people who cross the border illegally are caught. Those who are detained are returned to their country of origin. Many attempt the crossing again.

Those who do manage the initial crossing often find themselves vulnerable and in inhospitable terrain. In 2017 alone, a known 412 migrants died. While precise causes of death are often difficult to determine, most seem to be due to the elements: exposure, dehydration, and swollen rivers all play a role.

So why do people risk crossing the border from Mexico to the US without proper documentation? For some, they seek better economic opportunities than they might find at home. Others want to join (or in some cases, rejoin) family who already live in the States. And still others, especially from countries like El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, are fleeing horrifying violence, enduring a dangerous journey just to reach the border.

— Isabel Nerio Rodríguez, Matias Romero, Mexico 2018The only thing we want is security for our children. If our countries were safe, we wouldn't leave. Who would want to leave and suffer like this?

The future of the wall.

For opponents and supporters of President Trump’s plan to build a wall along the southern border, the future is uncertain. The amount of money needed to complete such a momentous infrastructure project has yet to materialize. If and when construction does start, it is estimated the border wall project will take at least several years to complete.

Americans will wait to see what happens. And for many migrants at the border, waiting simply isn’t an option.

The border wall 2017: a snapshot

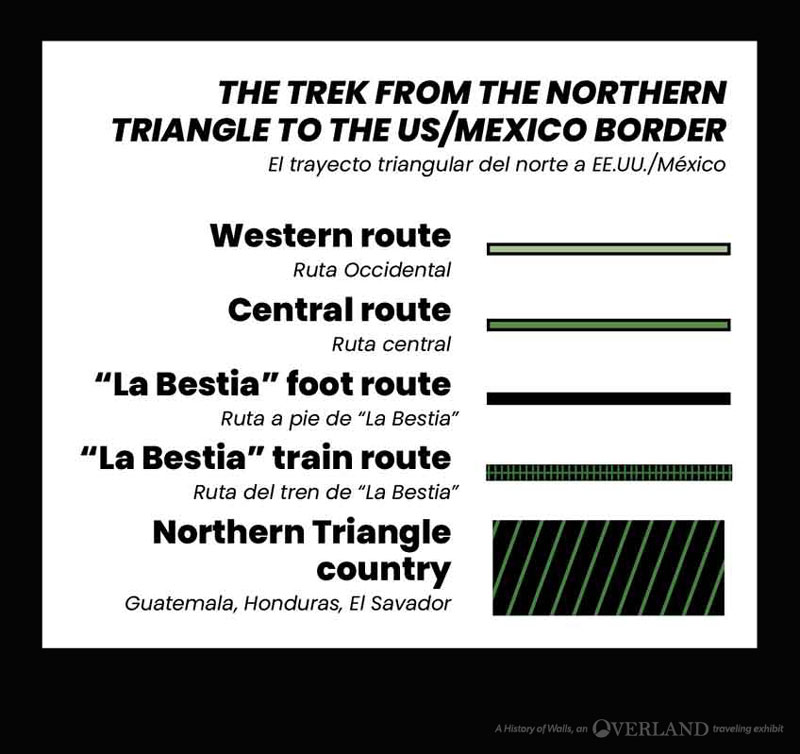

According the the US Border Patrol, in 2014 undocumented migrants from the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) outnumbered those from Mexico (239,226 to 229,178, respectively). Many of those Northern Triangle migrants were unaccompanied minors. These migrants crossed the increasingly militarized southern Mexican border, risking kidnapping, rape, and extortion from gangs, cartels, and corrupt officials before reaching the US/Mexico border.

For years many of these migrants would ride atop “La Bestia” (”The Beast”), a slow-moving freight train that runs from Mexico’s southern border to Saltillo. But officials have cracked down on the train, so migrants unwilling to risk violence and deportation must undertake the journey to the northern border on foot.

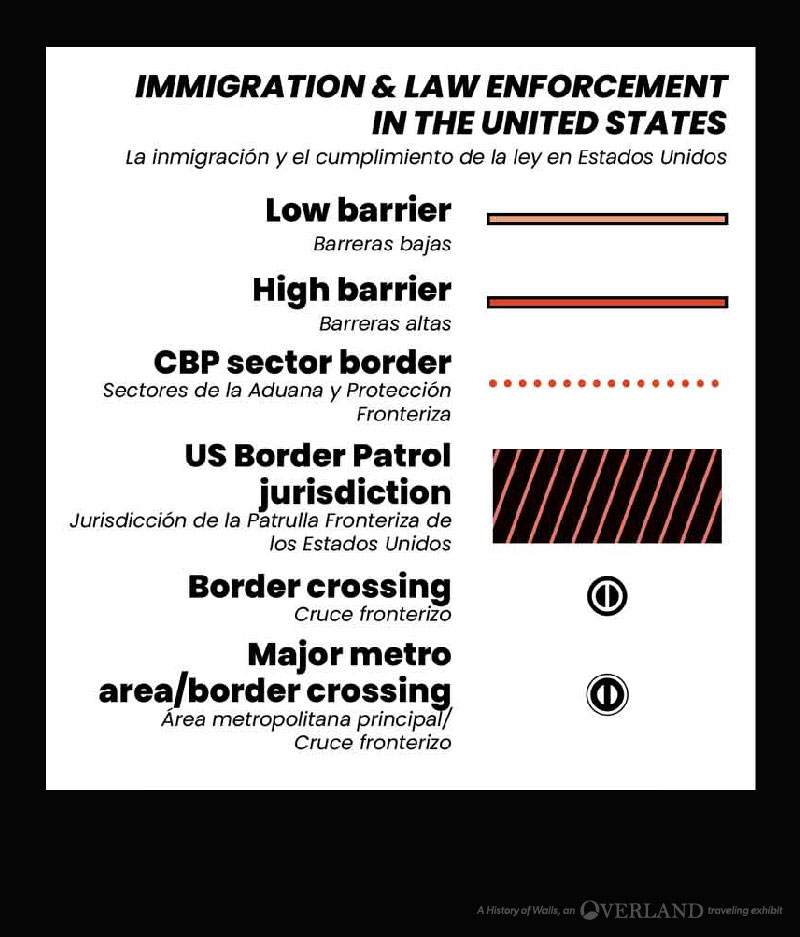

Of the over 1,900 miles of border shared by Mexico and the United States, only an estimated 700 miles are currently protected by some manner of physical barrier. (Most existing fencing has been built on public lands.) High barriers drive foot traffic to particular spots along the border; low barriers are erected in isolated, treacherous terrain to discourage driving across the border.