The Israel/West Bank Barrier

When does the story of the Israel/West Bank barrier wall begin?

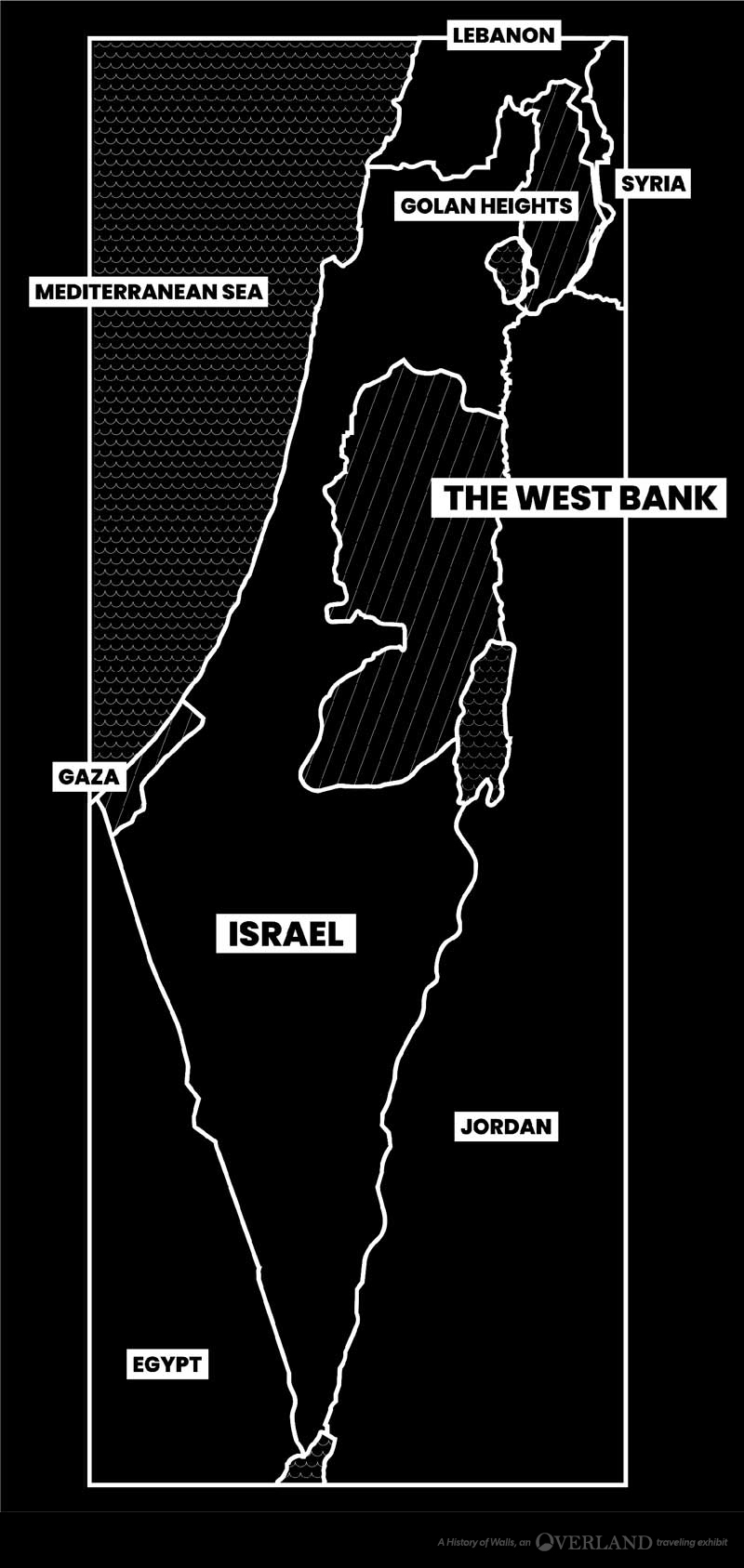

As with so many historical phenomena, it depends. You could start the story of the wall in 1967, after the resounding victory by the Israeli Defense Forces over Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in a conflict known as the Six-Day War, and the subsequent Israeli retreat back to the 1949 Armistice line, or what has become known as the “Green Line.” Speaking of 1949: You could start the story of the wall there, after Israel expanded its territory in the Arab-Israeli war of 1947-48.

You could start the story of the wall with the Zionist movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which saw tens of thousands of Jews moving to British-controlled Palestine in an effort to establish a Jewish homeland away from the antisemitism they encountered in Europe and Russia.

Or perhaps the story of the wall should start decades earlier, when Palestinian families began establishing homes in the lands west of the Jordan River. You could start the story with Mohammed’s ascent into heaven in al-Quds/ Jerusalem. You could start the story with the destruction of the second Temple by Rome in 70 CE and the subsequent Jewish diaspora to lands far from Judea.

Or you could start the story at the turn of the 21st century. While a barrier between Israel and the West Bank had been proposed by Israeli politicians as early as 1992, the Second Intifada of 2000 was the catalyst for the barrier’s construction.

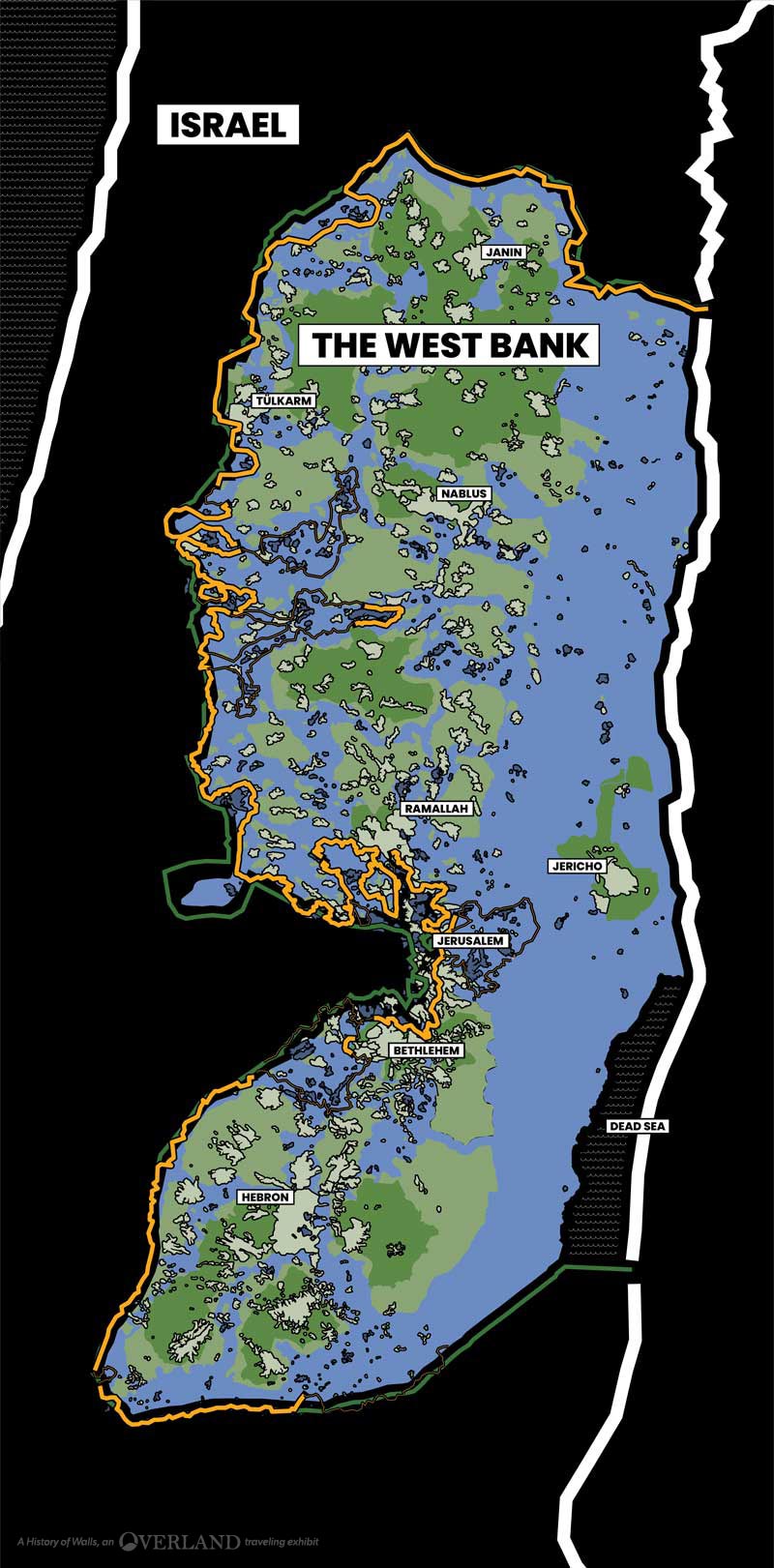

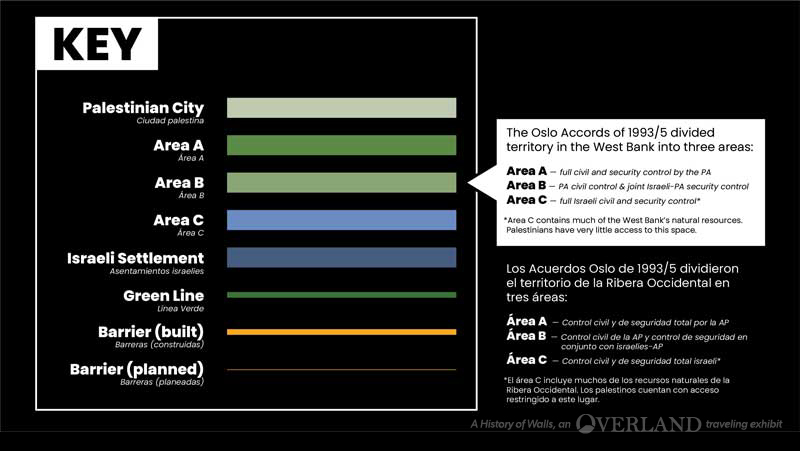

Between the Second Intifada—a Palestinian uprising that included rioting, the firing of mortar shells into Israel, and multiple suicide bombings—and the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks in America, the Israeli government, headed by Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, began building a “separation fence” in 2002 to frustrate potential terrorists from entering Israel. Over 80% of the barrier was built in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, which many Palestinians saw as a violation of the 2000 Oslo Accords signed by the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority (PA).

For the purposes of this exhibit, the story of the wall starts then.

Stopping Terror or Fracturing Palestine?

Nothing about the Israel/West Bank barrier is easy to understand: not its history, not its function, and certainly not its name.

The Great Wall of China, the Berlin Wall, Hadrian’s Wall: with time and perspective, the most famous walls of history have gained widely recognized and accepted names. The names for more recent borders are less established. In the case of the barrier between Israel and the West Bank, what you call the wall largely depends on which side of the barrier you’re on, and more specifically, what you believe the barrier is meant to accomplish.

Israelis generally call the barrier the “separation fence” (גדר ההפרדה), “separation wall” (חומת ההפרדה), or “security fence” (גדר הביטחון), all of which suggest a level of protection and distance from unwanted or dangerous elements.

For many Palestinians, the barrier is known as the “wall of apartheid” (جدار الفصل العنصري). This name recalls the governments of places like South Africa, where a majority of citizens were oppressed and marginalized—often violently—by a minority government.

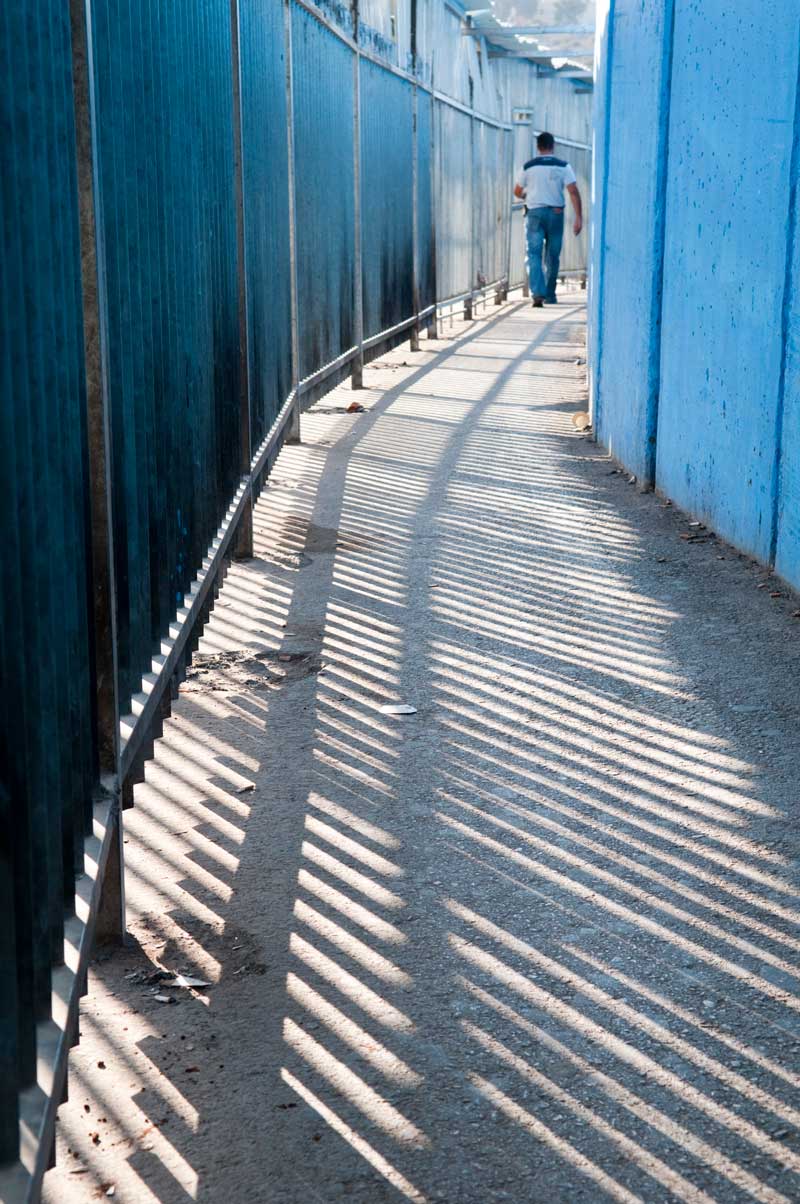

The construction of the barrier makes it no easier to figure out what to call it. In cities and more frequently trafficked areas, 25-foot high concrete walls dominate. In more rural settings, the Israeli government erected fences fortified with barbed wire. Patrol roads often run alongside, and high-end electronic sensors also monitor the area.

New facts on the ground.

Over 80% of the Israel/West Bank barrier is constructed on the Palestinian side of the Green Line, the internationally recognized border between Israel and the West Bank. Much of that fencing encloses Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Most of the international community considers these settlements to be in violation of international law.

The Israeli government has insisted the barrier was erected to protect its citizens from suicide bombings and other terrorist acts that accompanied the Second Intifada. While terrorism did decrease significantly after the barrier was built, scholars argue that the wall changes and reinforces the demographic realities on the ground, and makes it impossible for Palestinians to reclaim the areas beyond the barrier wall in any future peace negotiation.

Barrier to War, Barrier to Peace

What does the Israel/West Bank barrier do?

By severely restricting Palestinian movement from the West Bank to Israel and back, the Israeli government has been able to significantly reduce terrorist acts. (That reduction also coincides with the cooling and eventual end of the Second Intifada in 2005.) Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has suggested that to remove the wall would only encourage a renewed influx of terrorists, saying in a 2009 speech,

— Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, 2009I hear they are saying today that because it’s quiet, it’s possible to take down the fence. My friends, the opposite is true…It’s quiet because a fence exists.

For Palestinians, the barrier has a profound effect on their government’s ability to effectively administer basic services. If there is a crisis in a city and that city is cut off from the rest of the West Bank by the barrier, it may well take hours for them to receive help. The barrier also makes it extremely difficult for Palestinians to access land they own on the other side of the wall. Farms go untended and businesses wither, strangled by the wall.

For many Israelis, the barrier is understood to protect their families and homes from terrorism. For many Palestinians, the barrier stands as a symbol of oppression and aggression by and occupying power.

The wall and the future of Palestine.

Since September 2014, no further progress has been made on the construction of the barrier wall, leaving completed construction at under 70%. While the wall impedes daily life for many Palestinians, it is by no means an impermiable barrier; many Palestinians go to and from work in Israel on a daily basis, though the wait to get through can sometimes be long.

No doubt the next time Israeli and Palestinian leaders sit down to talk peace, the Israel/West Bank barrier wall will be a key part of the conversation.

Israel/West Bank Barrier Illustrated

Among the many impediments to a lasting peace agreement between Israel and Palestine is the situation on the ground, as illustrated here.

Israel is unlikely to accept any agreement that displaces a significant number of Israeli settlers.

Palestine will likely demand a contiguous, sovereign state and will not cede any more land to Israel.

What is to be done?