Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China isn’t a single wall at all.

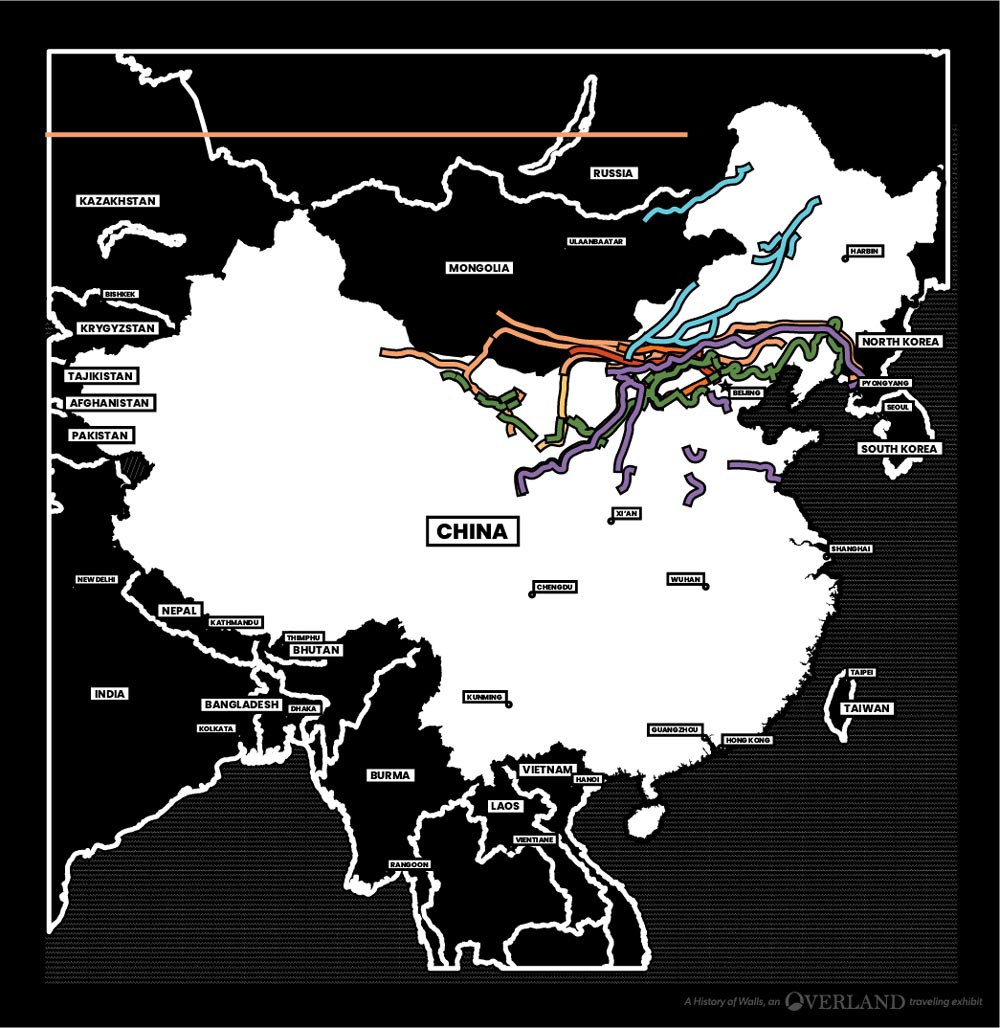

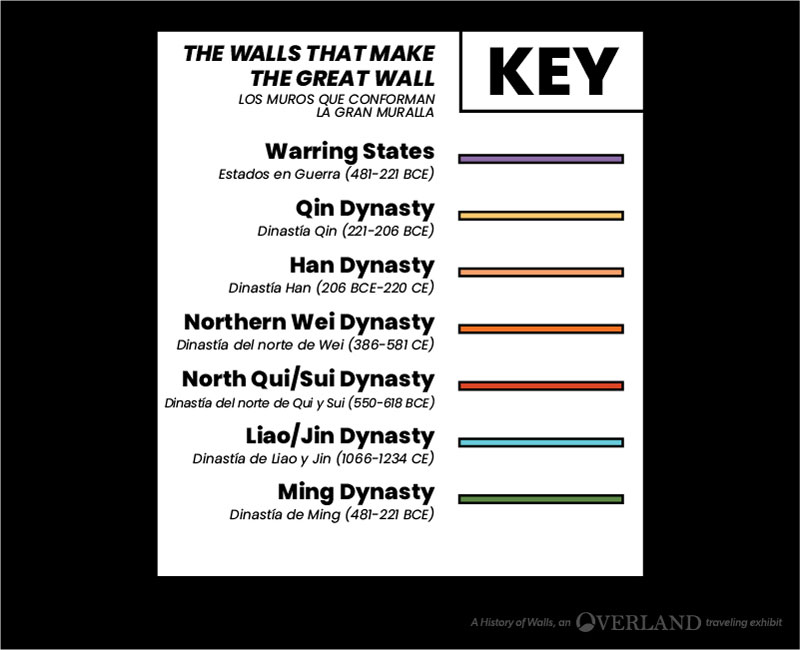

Rather, it’s a collection of walls built by Chinese emperors over a period of nearly 2,000 years, from about 220 BCE to 1644 CE. (The Great Wall also incorporated walls built during the Warring States period some 200 years before.) The first sections of a comprehensive wall were built during the Qin dynasty, and spanned a good deal of the northern and western expanses of China. Some estimates suggest the Great Wall winds over 13,000 miles, including trenches and natural barriers.

Over the next millennia, dynasties came and went, and each one had its own approach to wall-building. Some, like the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), ignored the walls, trusting instead in diplomacy to keep China safe. Emperors from the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) repaired and modified existing walls from earlier eras.

From 1368 through 1644 CE, the Ming dynasty undertook the greatest expansion and reinforcement of the Great Wall, building many of the iconic sections that come to mind when we think of the Great Wall of China. For many years after the fall of the Ming dynasty, the Great Wall of China fell into disrepair and obscurity. Desertification damaged and corroded western sections of the wall. Bricks were taken from sections to be used in other building projects. Weeds grew in the cracks. In many places the landscape swallowed the wall entirely.

Today, the Great Wall of China is still under threat. While tourists frequent restored Ming-era sections of the wall, other sections are in disrepair and are under threat from development and environmental degradation, despite governmental protection and the wall’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

What did the Great Wall accomplish?

The easy answer is that the Great Wall of China kept others out. The wall made it difficult for the largely nomadic peoples who lived on the steppes to the north or the forests to the northeast of China—for instance, the nomadic communities of the Xiongnu and Mongol, or the Manchu peoples to the north of what is now the Korean peninsula—to push into Chinese territory or raid Chinese settlements.

At least, that was what the wall was meant to do. While the Great Wall was certainly formidable, there were often gaps in the wall. If an invading force didn’t want to go over or through the wall, they could sometimes go around. In some cases, local officials could be bribed. Those officials would then allow the invading army safe passage through one of the passes in the wall.

The Great Wall: Keeping Out, Bringing In

Great Wall, greater reach.

The walls built at the behest of the emperors weren’t always meant to keep someone or something out. Though many walls were built with the objective of policing the movement of people from one place to another—excluding outside threats and protecting citizenry and resources within—in some cases, a newly built wall would bring something into the empire: new territory.

Early Warring States dynasties (700-221 BCE) such as those headed by King Zhao of the Yan state (325-299 BCE) built walls far beyond their borders. In effect, the state was claiming new territory with the wall by moving the border outward.

Names for the Great Wall.

For most of its existence, the Great Wall wasn’t considered a symbol of national pride or an incredible feat of engineering or construction. Rather, for much of its first 2,000 years the wall was synonymous with pain, sorrow, and oppression.

The original term for the wall was 長城 (changcheng) or “Long Wall.” The name was associated with mistreatment and political violence by the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE), and dynasties afterward used different terms for the wall to distance themselves from that perception.

In some cases, names for the wall reflected the realities of its construction and shape. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), one of the many names for the Great Wall (a term few if any used in those days) was “the Nine Border Garrisons,” reflecting the scattered, defensive nature of the wall during that period.

Whether it was called “the frontier,” “rampart,” barrier,” “garrison,” or “border wall,” for Chinese poets the Great Wall was a symbol of sadness and isolation. Known as “frontier verse,” poets would write from the perspective of a person living in the shadow of the Great Wall, on the edge of the Chinese empire.

From I Watered My Horse at the Long Wall Caves

— Chen Lin (?–217 CE)I watered my horse at the Long Wall caves,

water so cold it hurt his bones;

I went and spoke to the Long Wall boss:

“We're soldiers from Taiyuan—

will you keep us here forever?”

“Public works go according to schedule—

swing your hammer, pitch your voice in with the rest!”

A man’d be better off to die in battle

than eat his heart out building the Long Wall!

The Long Wall—how it winds and winds,

winds and winds three thousand li;

here on the border, so many strong boys;

in the houses back home, so many widows and wives.

What the Great Wall Means Today

The Great Wall has been reclaimed but is still under threat.

During the Cultural Revolution of the mid-20th century, the Great Wall, like much of imperial Chinese art and culture, was looked upon with scorn or disregard. This new and often brutal era of Chinese politics, headed by Mao Zedong, encouraged the people to "allow the past to serve the present." Pieces of the wall were repurposed for other building projects or knocked down to make way for new construction.

It wasn’t until Deng Xiaoping started the “Love Our China and Restore Our Great Wall” campaign during the 1980s that Chinese people began to see the Great Wall as a vital part of their country’s history and culture. Since then the Great Wall has played a prominent role in China, including a cameo in the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympics hosted in Beijing.

Despite the revival of the Great Wall as a source of national pride, many sections are still under threat from environmental degradation and neglect. In fact, in the rush to capitalize on tourist dollars, visitors may be doing as much to harm the Wall as protect it, adding exceptional wear and tear on an already fragile architectural artifact.

China is building a new Great Wall.

Governed by a one-party system intent on stifling dissent and controlling the flow of information to its citizens, China has responded to the advances of the web by closely monitoring and in many cases censoring the global internet. Sites that seem ubiquitous in most of the rest of the world—Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, the New York Times—are unavailable through traditional means in China. The Chinese government’s chokehold on the web is facilitated by a new Great Wall: The Great Firewall of China.

In the early days of the internet China was relatively open to new information streaming into the country. The mid-1990s to 2000 saw a period of relatively free exchange on the web. After 2000, the Chinese government begin to tighten its grip on the flow of information into the country with the Golden Shield Project, a surveillance program that laid the foundation for the Great Firewall.

China’s pursuit of “cyber sovereignty” continues today. The unprecedented restriction of the internet is the work of over 50,000 state-employed censors, various filters and algorithms, and a good deal of self-censorship on the part of Chinese social media companies, which are held responsible for the content their users create.

As of 2017, Freedom House rated China as the “World’s Worst” with regards to online freedom, beating out countries like Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Russia for a place at the top (or bottom, depending on your perspective) of the list. After a period of openness to Western ideas and information, with the advent of the Great Firewall, China has begun to close its digital doors.

- attrib. Genghis KhanThe strength of walls depends on the courage of those that guard them.

Contemporary Borders, Ancient Walls

Though many of the Chinese dynasties that ruled over the last two millenia chose to construct new walls and/or maintain existing walls built by previous dynasties, some rulers elected to use other political means to keep outside forces in check.

Of the major dynasties that chose not to pursue wallbuilding as an agenda, the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) held on to existing territory and expanded the Chinese empire greatly without building new walls or utilizing existing ones.

For most of the world, the term “Great Wall of China” is synonymous with crenellated stone walls winding over dramatic mountain ranges.

In fact, of the 13,170 miles of wall in China, many are modest and crumbling, hidden by the landscape, worn down by weather and disrepair, and in many cases, lost to time.