Berlin Wall

For nearly 30 years, no one place embodied the anxiety and tension of the Cold War quite like the city of Berlin.

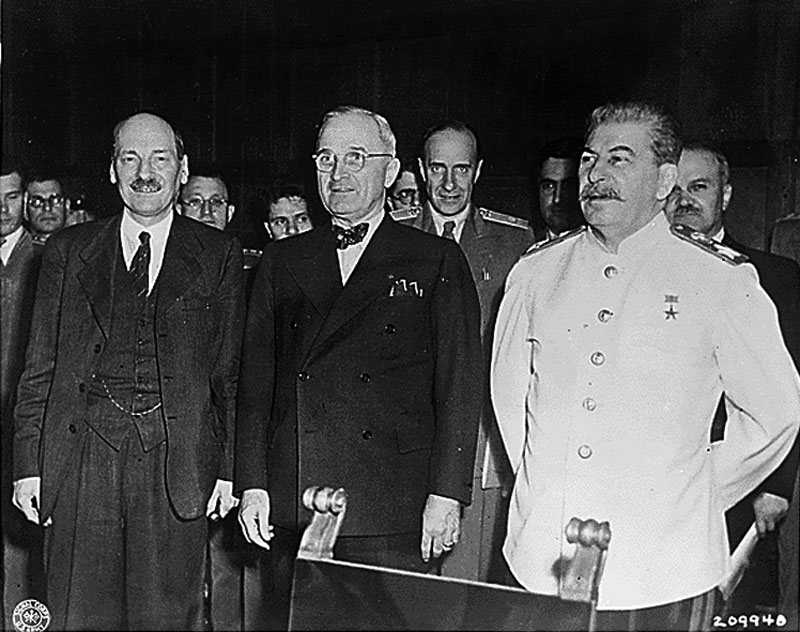

After the defeat of Nazi Germany by Allied forces, leaders from the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union gathered at the Potsdam Conference in August of 1945 to finalize plans for Germany going forward.

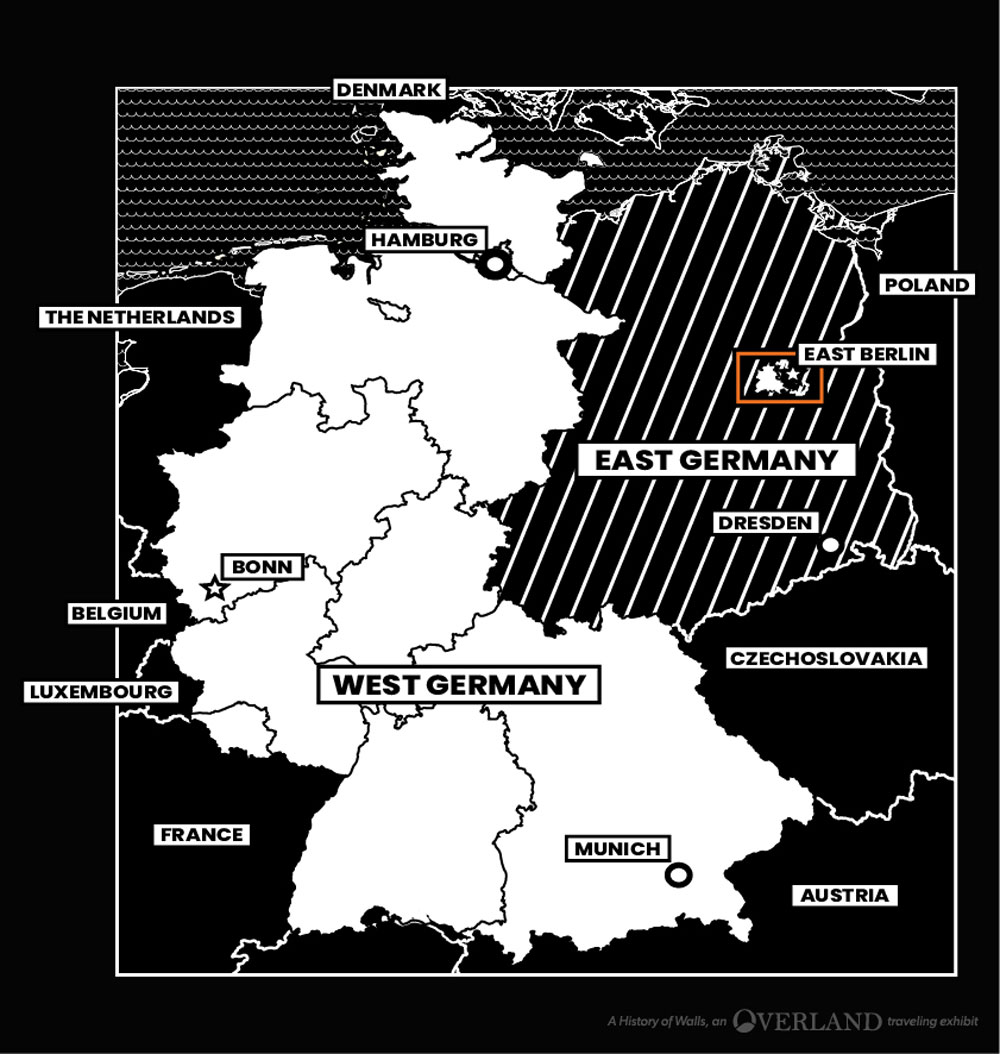

In the end, Germany was divided into occupation zones controlled by individual Allied countries. The Soviet Union maintained a hold from the Oder river to the Western Occupied Zones. The United States occupied the southern portion of Germany, the British occupied the north, and France took control of far western sections.

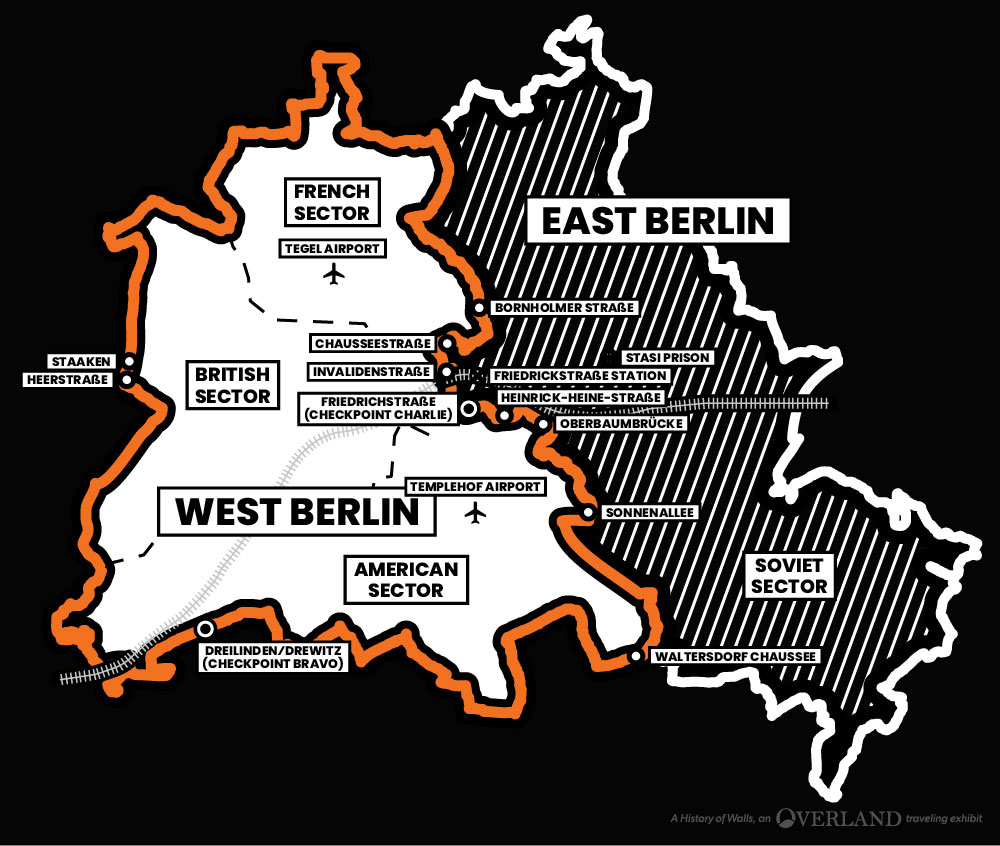

Isolated in the middle of the Soviet-controlled occupation zone, Berlin became a microcosm of the larger situation in the post-World War II world. Like Germany as a whole, Berlin was divided into four occupation zones. Communist politics and practice dominated in East Berlin, while in West Berlin, the American, British, and French sectors practiced free market capitalism. These four countries, once united by the common goal of defeating the Nazis, now jockeyed for control, feeling their way toward a new, tenuous balance of world power between capitalism on one side, and communism on the other.

While Berlin was divided between the Soviet sector in the East and the American/British/French sectors in the West beginning in 1945, it wasn’t until August of 1961 that East Germany began construction on what would become known as the Berlin Wall. That particular place and moment in time captured the tension between communist and capitalist ideologies that would define the second half of the twentieth century.

The Berlin Wall: Closing the Iron Curtain

Many walls are built to keep people out. The Berlin Wall was built to keep people in.

In 1949, while the newly formed, Soviet-backed German Democratic Republic (GDR) strengthened their borders with the capitalist, NATO-friendly Federal Republic of Germany, Berlin remained comparatively open. East and West Berlin shared roads, sewer systems, railways and power grids. People passed from East to West (and vice versa) to go to work and visit family with very little difficulty.

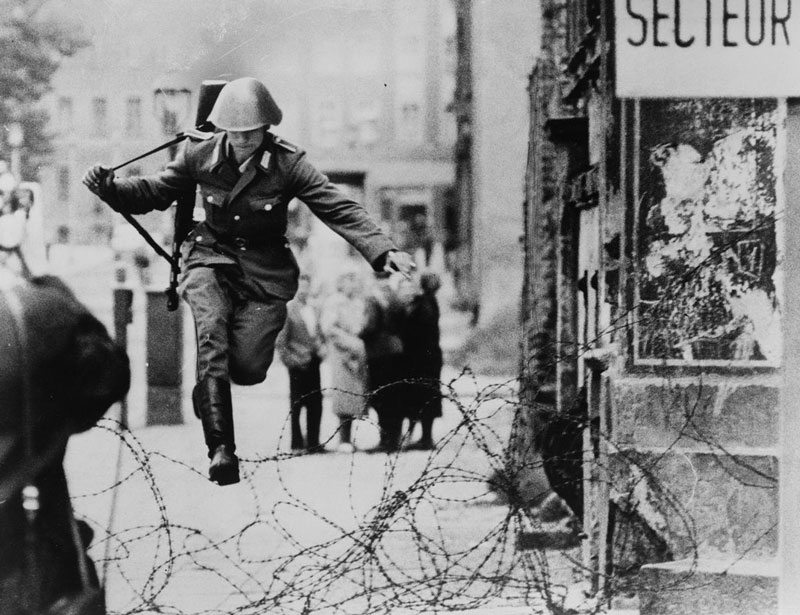

That changed on August 12, 1961. Alarmed by the number of East German intellectuals and skilled laborers that were leaving for the west, East German leader Walter Ulbricht, with the backing of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, ordered the borders in East Berlin closed and hardened.

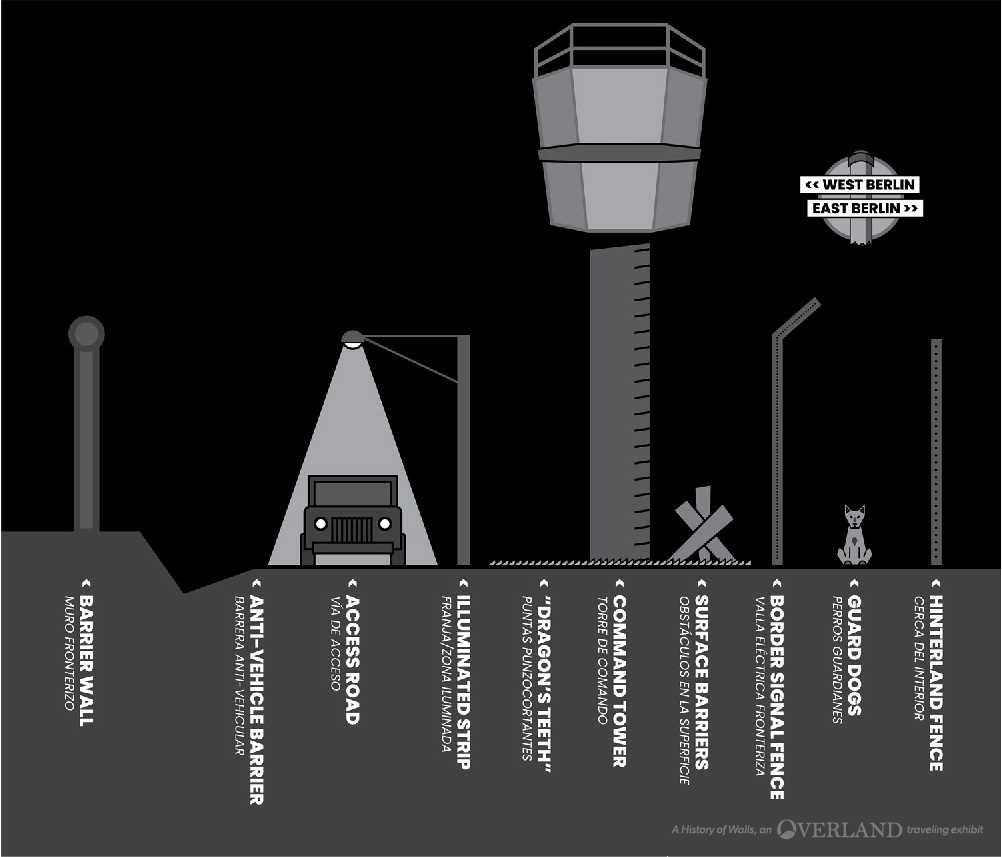

Fences were erected, and later replaced by a 12-foot tall concrete wall, fronted by a 100-foot “death strip,” an open space littered in places with land mines, guard dogs and watchtowers. East German guards were ordered to shoot those who attempted to escape (an order known as the Schießbefehl). What was once the easiest place for Eastern Bloc citizens to escape to the west, suddenly became one of the most difficult.

The human cost.

The Berlin Wall divided communities, families, and friends. It confined a group of people who, in many cases, wanted desperately to get out. Crossing the border from East to West Berlin was a potentially deadly proposition. Nevertheless, people tried—and sometimes succeeded. One person crossed by stealing an armored vehicle from the East German army and driving it through a portion of the wall. Others attempted escape by hot air balloon and by navigating the sewers below Berlin’s streets. Over 5,000 people successfully defected from East to West Germany from 1961 to 1989.

Many weren’t so lucky. While an official count is difficult to come by, somewhere between 98 to 200 people were killed attempting to cross the wall.

— John F. Kennedy, West Berlin, 1963...It is, as your Mayor has said, an offense not only against history but an offense against humanity, separating families, dividng husbands and wives and brothers and sisters, and dividing a people who wish to be joined together.

When the Wall Came Down

Pressure cracks the wall.

For nearly 30 years the Berlin Wall stood, bristling with menace, an embodiment of the threat of total annihilation posed by the Cold War. In 1987, with tensions slowly easing and the Soviet Union beginning to open itself ever so slightly to the rest of the non-communist world, US President Ronald Reagan stood in front of the Brandenburg Gate and delivered a speech which included the now-famous lines, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

While American and European opposition aided in hastening the fall of the German Democratic Republic, it was the people of East Germany who finally put fatal cracks in the Berlin Wall. What started with the collapse of communism in Hungary in May 1989 arrived in East Germany, as an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 protesters jammed the Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989 to demand democratic reforms from GDR officials.

As foreign intelligence head Markus Wolf stood to speak on behalf of the government, protest leader Bärbel Bohley recalled: “When I saw that his hands were trembling because the people were booing I said to Jens Reich: We can go now, now it is all over. The revolution is irreversible.”

On the evening of November 9, 1989, a badly bungled rollout of a new East German open border policy inspired East Berliners to head to border crossings along the wall. GDR guards, confused, overwhelmed, and without clear orders from their government, opened the gates, and East Berliners poured over the border into West Berlin. There was champagne. There was dancing. People climbed the walls and began demolishing them. The Berlin Wall, cracked as it was, began to fall that night.

A reunified Germany.

The reunification of Germany happened rapidly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The East German economy collapsed, and East and West Germany moved quickly toward economic reunification, with West Germany providing much needed support to the failing communist state. A reunification treaty, in which East Germany would be absorbed by West Germany, was signed on August 31, 1990. The two countries became one on October 3 of that same year.

To this day, pieces of the Berlin Wall stand in the German capital and around the world as a reminder both of the profound cost of oppression, as well as the triumph of the human spirit.

The Two Berlins, 1961

Despite the extensive fortifications of the Berlin Wall, nearly 5,000 industrious and brave East Germans found a way into West Berlin, and from there, to the world beyond the Iron Curtain.